On this day, May 26, 1914, Theodore Roosevelt delivered a report to the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., detailing his journey down the River of Doubt. Following the harrowing journey, Roosevelt was physically weak from the injury and illness that nearly ended his life. Mentally, he was driven to push forward by sheer willpower, as he had been since he was a little boy. It was imperative that he explain the significance of what he had done.

Roosevelt suffered a bitter defeat in the 1912 presidential election, amplified by his guilt and anger at having contributed to Woodrow Wilson’s victory. As he often did, Roosevelt decided to literally outrun his grief by escaping on an adventure in the wilderness. He received a serendipitous invitation to undertake a speaking tour in South America, which he decided to supplement by arranging a natural history expedition in the name of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). Although he had initially planned to undertake a journey along a known and mapped river, he was convinced by the Brazilian Minister of Foreign Affairs Lauro Müller and military telegraph engineer Colonel Cândido Rondon to descend an unknown and treacherous river in the Amazon Basin. Rondon had discovered the headwaters a few years prior and was eager to map the entire river. Ever since he was a young man, Roosevelt had been adventurous to the point of recklessness, and he had always harbored a love of scientific fieldwork. He wrote to the AMNH, whose officers were horrified and threatened to disavow him, that he was quite prepared to leave his bones in South America if need be. Roosevelt, Rondon, and George Cherrie of the AMNH began preparing for the expedition.

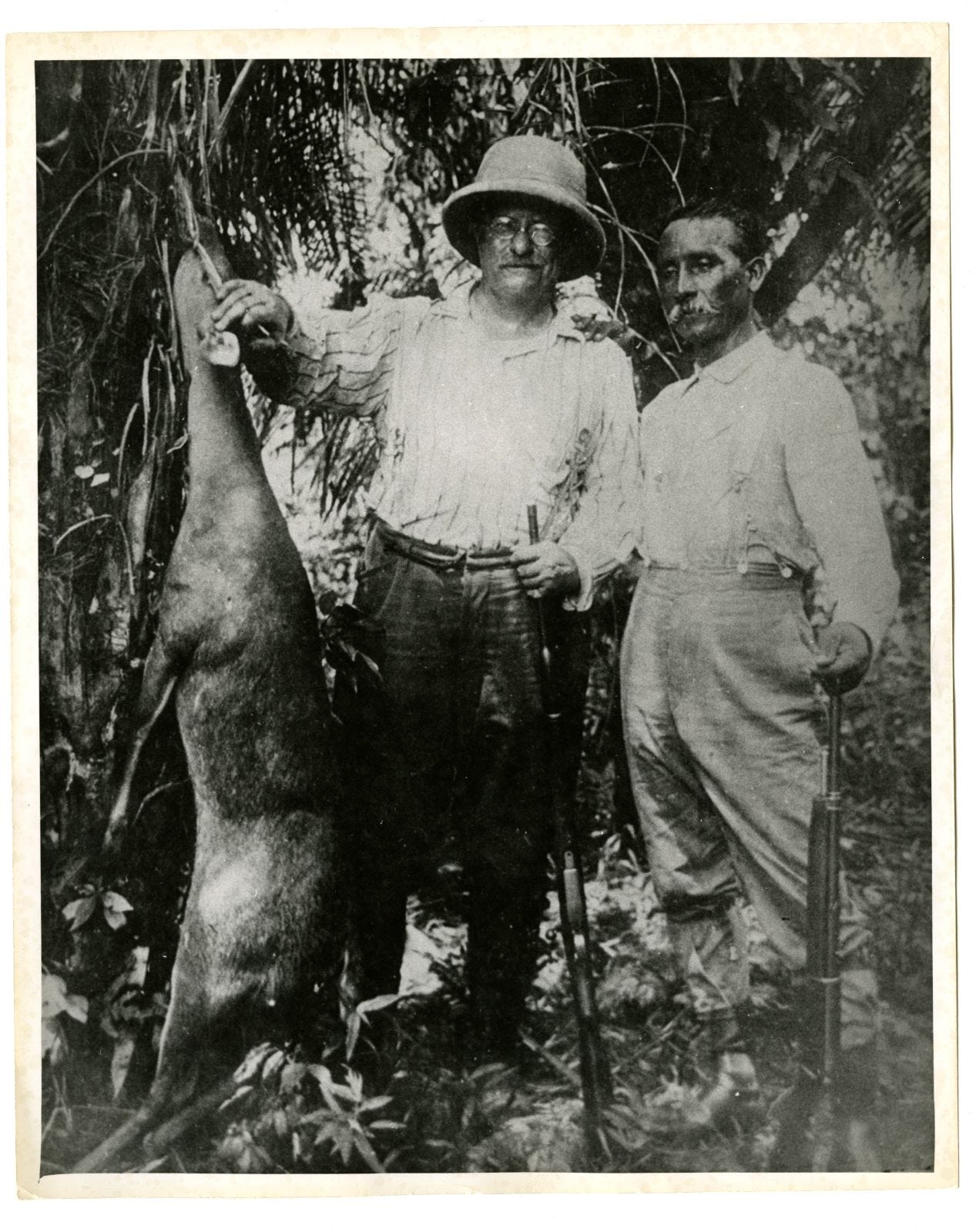

All involved knew they would face hardship and privation – some would argue that Roosevelt wanted to face those kinds of experiences. Still, even having sought it out, no one could have predicted just how perilous their adventure would turn out to be. The Amazon Jungle is a cruel, unforgiving environment. At every turn, the men were threatened by stinging insects, vicious beasts, festering bacteria, searing heat, drenching rain, hostile natives, enveloping darkness, and the river’s raging rapids. Unpredictable and unrelenting, Mother Nature battered the expedition as the days became weeks became months. Nearly all of the men, Roosevelt and his son Kermit included, were beset with malarial fever. To make matters worse, Roosevelt sliced open his right leg on a rock in the river, and the resulting infection kept him barely clinging to life for weeks. When they finally reached the end of the river, Roosevelt was drifting in and out of consciousness, had lost a quarter of his body weight, and could barely move or speak.

As the reports reached the United States and Europe that Roosevelt claimed to have discovered an entirely unknown river nearly a thousand miles long, skeptics began to challenge him. It could not possibly be as large a river as he claimed, they said. It might not even have been a real river at all, but flooding in the forest, others argued. Roosevelt, who had gone through hardship like he had never experienced before to make the voyage and live to tell the tale, was incensed. Not only for himself, but for the sacrifices of the Brazilian men who did the hard work of the voyage, including two who gave their lives – one swallowed up by the river, and another murdered. And so, only a few weeks after reaching the end of the adventure, Roosevelt determined to deliver a detailed report to the National Geographic Society, so as to silence the naysayers.

When he arrived in Washington, Roosevelt had recovered some, but was still showing visible signs of illness and fatigue. Driven by (and perhaps barely concealing) his righteous anger, Roosevelt began his address by noting that it was being taken down verbatim by a stenographer because he did not expect the journalists to represent the exacting details and their consequences fully. “What I have to say is a matter of real moment, and I wish to put before this audience the exact description of what we have done,” he said. “It is going to be taken down stenographically, so that I will not have to trust to the well-meaning but not necessarily wholly successful efforts of the gentlemen who write headlines in the newspapers, to combine color with thrill.”

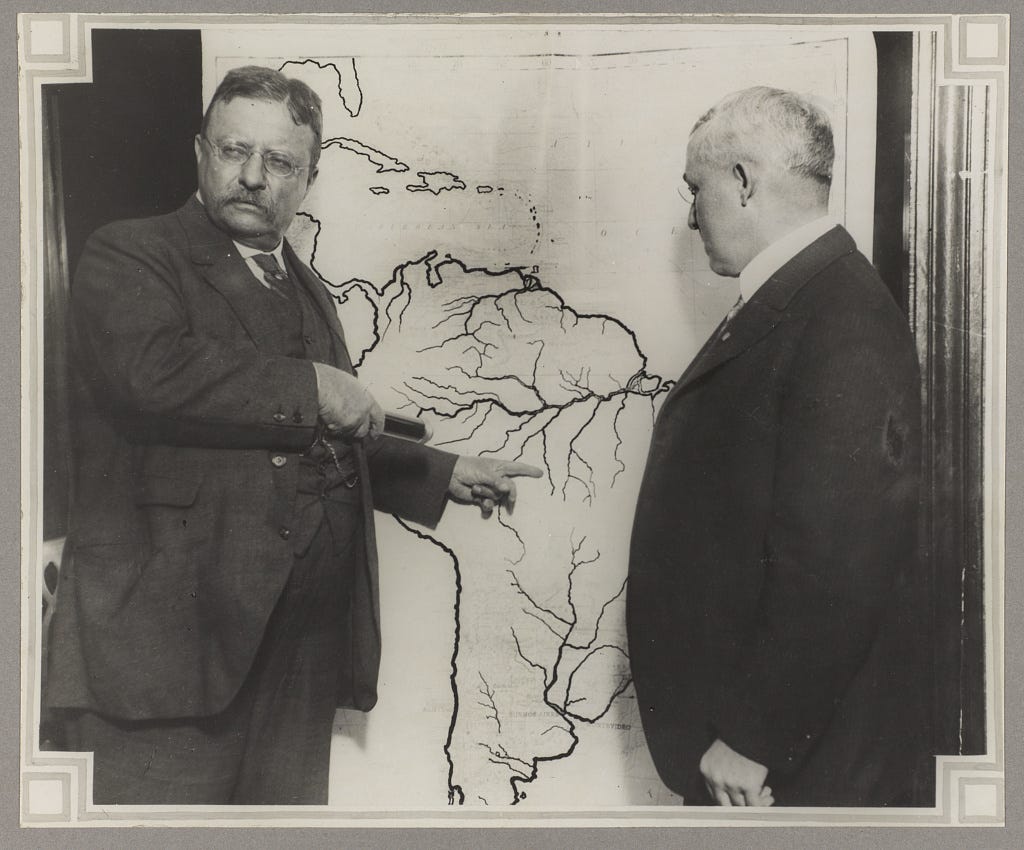

After praising the work of those explorers who came before him, and relating conversations he had had with other explorers and mapmakers regarding the discovery, Roosevelt began to argue his points strenuously. “We found a river,” he said, pointing to it on a revised map, “with no hint or suggestion on the map. I repeat that there is not a hint or a suggestion.” He went on to explain between which degrees of longitude and latitude it was located, and the cardinal directions in which it flowed. He immediately returned to insisting that the river had been previously unknown, except in small portions to the Cinta Larga people who lived in its valley, and a handful of rubber harvesters. “We have put on the map a river of which there is not only no knowledge and which is not shown on any existing map, but it is not even guessed at on any existing map; of which the lower portion had been known for years by rubber men, but of which no topographer had the faintest idea of the existence, and of which not a trace is to be found on any existing map.” Although Roosevelt often chafed at any suggestion that he felt a need to protect his ego, there can be no doubt that he was here nursing the bruises made by those who doubted him.

Roosevelt went on to suggest that the best way to prove what he had done was to send further expeditions to make additional surveys of the river. He pledged to offer his support and advice to those who would undertake the perilous journey. (Such a journey was finally undertaken in 1927, led by British explorer George Miller Dyott, who did in fact confirm the findings of the Roosevelt-Rondon Expedition.) To emphasize just how difficult such an expedition would be, he began relating what his own expedition had gone through. He told of canoes lost to the rapids, of the near-starvation diet they were reduced to, of how their clothes had been reduced to rags, and even how Colonel Rondon’s dog had been shot with arrows by a contingent of the Cinta Larga people. After telling all of these tales – what some believed were tall tales before that night - he reminded the thousands of men listening that they must remember his “exact language” of the report. In doing so, there should no longer be doubt in anyone’s mind of the magnitude of what he had done.

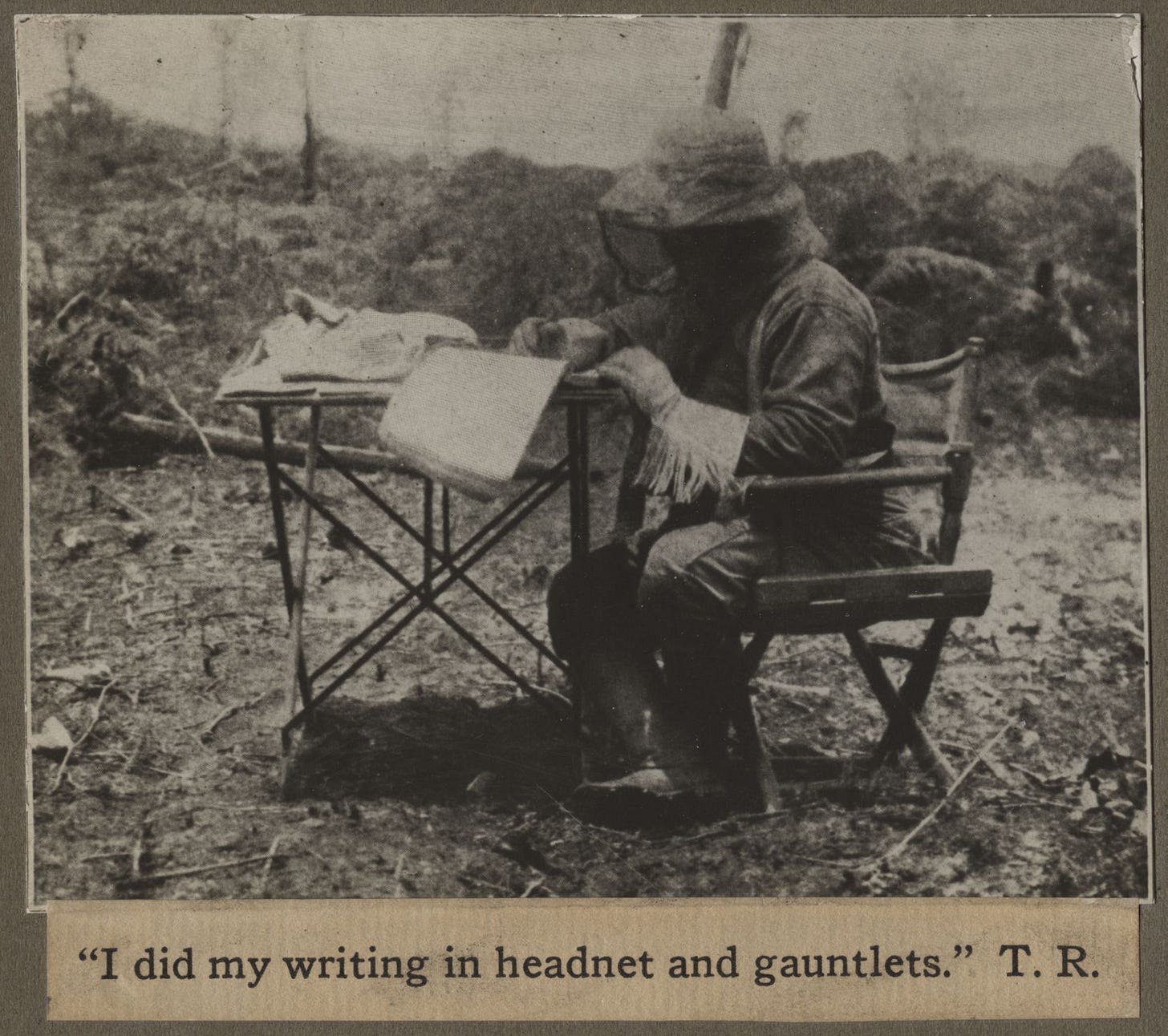

In addition to reporting to the National Geographic Society and the Royal Geographic Society in London, Roosevelt produced a book, Through The Brazilian Wilderness, published by Scribner’s in 1914. Despite the danger and hardship, Roosevelt spent much of the trip writing out the entire book in pencil.