On this day in 1880, Theodore Roosevelt graduated from Harvard College with a Bachelor of Arts degree. Although he (and others) sometimes felt he was mediocre academically, he would graduate magna cum laude. He was ranked 21st in his class of 177.

Roosevelt did not have a major - or a concentration, as Harvard calls them. (Harvard’s first concentration, History and Literature, was introduced in 1906.) He was, however, able to guide the course of his education through the use of electives. Throughout his four years of study, Roosevelt took science courses, and in particular natural history courses. A student of wildlife since childhood, he hoped to become a professional naturalist. His best marks were consistently earned in natural history courses.

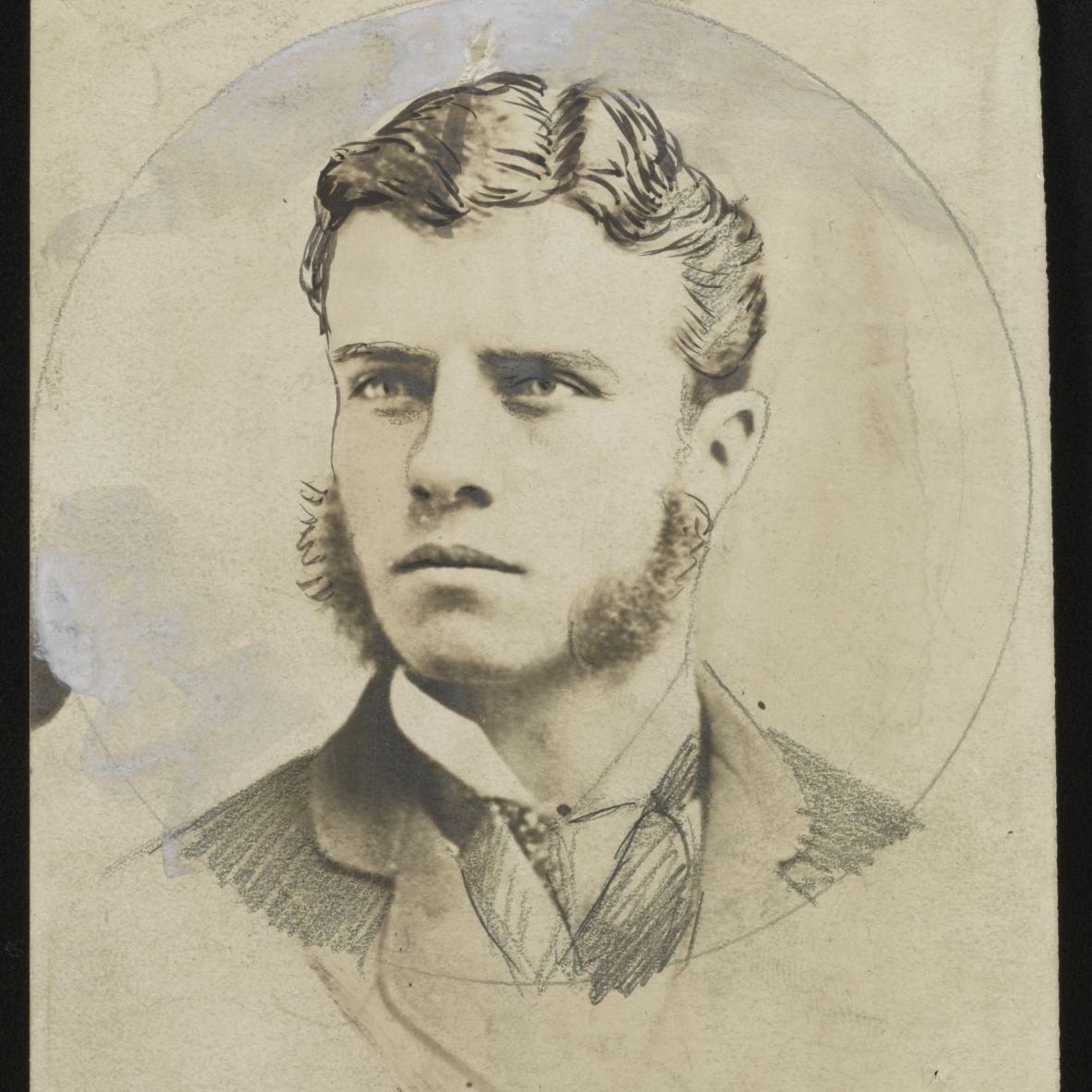

Roosevelt’s freshman year, beginning in 1876, was marked by bursts of what is now so often referred to as Rooseveltian energy. (Well, so was all of his time at college, really). He took up boxing and wrestling, and he studied with the same intensity that he fought. He became a dandy and a social butterfly – although he was something of a snob and would initially associate only with those he deemed of the correct class. In his courses, he became known for strenuously arguing with his instructors. He scheduled his day down to the hour so that he could be certain that he would invest the necessary time and effort into everything he wanted to pursue.

Outside of the classroom, Roosevelt was just as energetic and ambitious. He spent his summers back in Oyster Bay, Long Island, where he engaged in both exercise and expeditions. In the summer of 1877, Roosevelt wrote and published his first work, The Summer Birds of the Adirondacks, with the help of his best friend Henry Davis (“Hal” or “Harry”) Minot. Although he didn’t realize it at the time, Roosevelt would later reflect on this work as the beginning of his career as a professional author. More than politics or hunting or anything else, writing came to be the work that defined him.

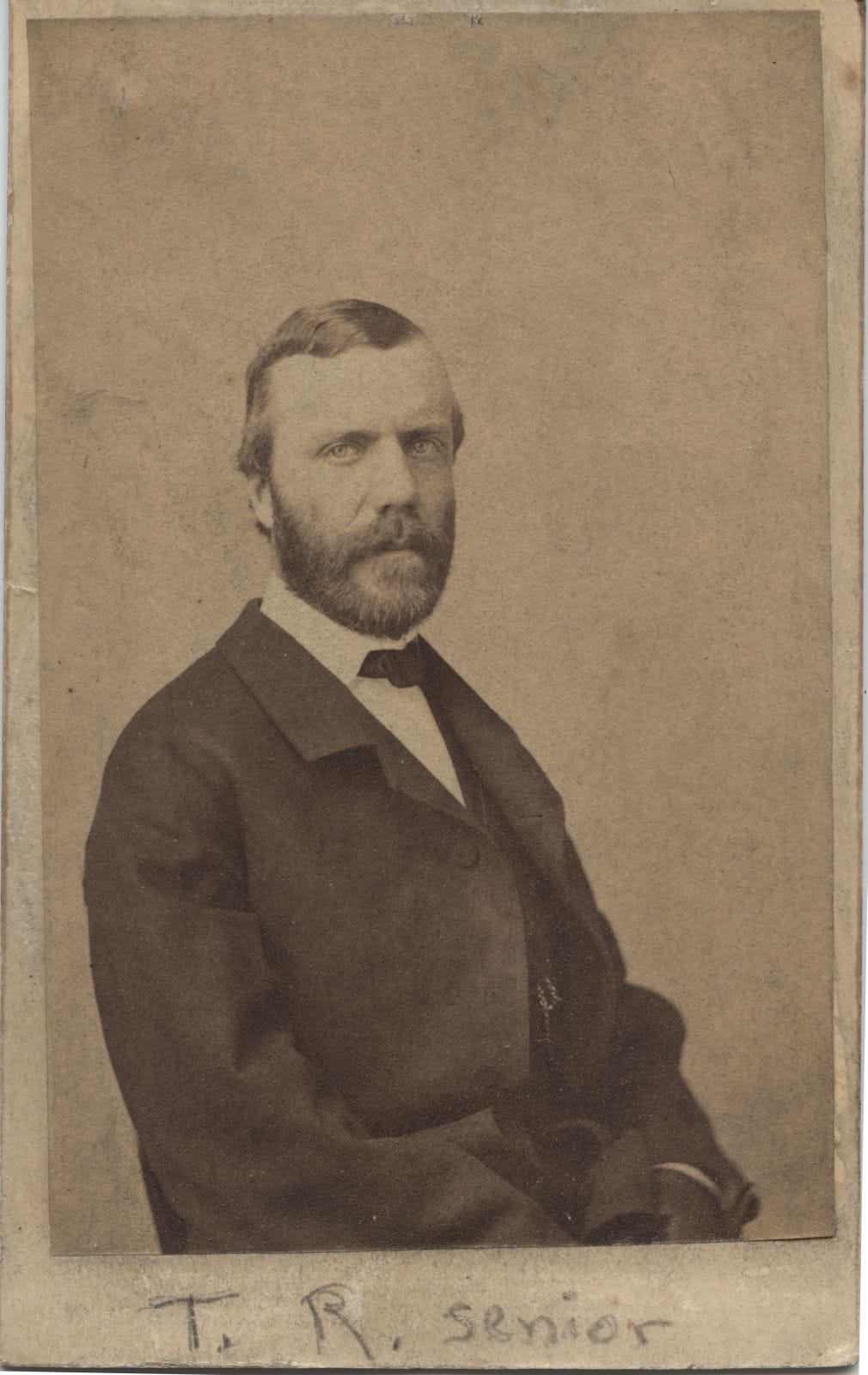

In the winter of 1877-1878, during Roosevelt’s sophomore year, his father Thee's health began to deteriorate, perhaps due to the stress of his political work. He experienced severe stomach cramps, and he collapsed in December. The situation did not improve, but he hid the severity from his son. On February 9, 1878, Roosevelt received word that his father was on his deathbed. He rushed to take the next train from Cambridge to Manhattan but arrived several hours too late to say goodbye. Thee had died, at only forty-six years old, of a bowel tumor.

Roosevelt was lost without his father, his greatest hero. His diaries contain outpourings of grief for months following Thee’s death. The only way he could overcome this grief, he found, was to throw himself headlong into his studies and his physical activities. He scored some of his best examination marks the following week. He dutifully taught Sunday school. He rowed and rode in Oyster Bay. This served the purpose not only of distracting him from dark thoughts but also of honoring his father’s memory by becoming the kind of man he would have been proud of. (Roosevelt continued the practice of literally working through his grief throughout life, especially during his time ranching in North Dakota. “Black care rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough,” he wrote in his 1888 work Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail.)

Just as he had recovered from one heartbreak, he experienced another. It had long been assumed that Roosevelt was destined to marry his childhood sweetheart, Edith Kermit Carow. From an early age, they had bonded over intellectual pursuits, with Roosevelt writing that Edith was the “most cultivated, best-read girl” he knew. Even as he began to casually express interest in other girls, he bristled at suggestions he might choose any of them over Edith. But in the summer of 1878, they unexpectedly broke up. We have no clear evidence as to what happened. All we know is that they frolicked on Long Island for several weeks in August, celebrating Edith’s seventeenth birthday. But after a visit to the Roosevelt family summer house, called Tranquility, they parted ways. Roosevelt was so disturbed that two days later, he shot a neighbor’s dog while out on a horseback ride.

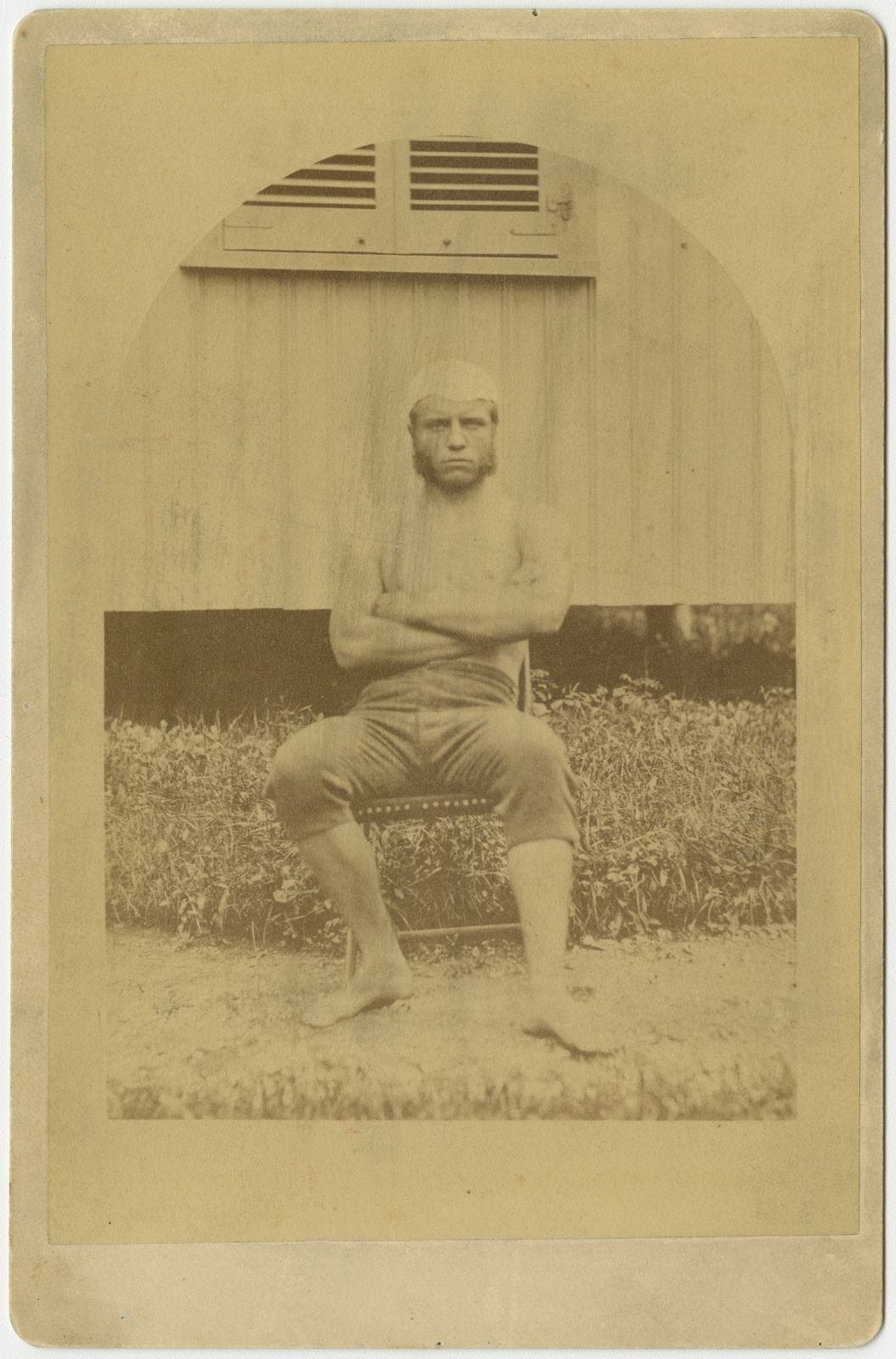

As before, Roosevelt decided to outrun his grief. He spent the remainder of his vacation hiking and hunting in the North Woods of Maine, guided by lumberman Bill Sewall and his nephew Will Dow. Both men of physical prowess and strong moral character, Roosevelt found much solace in their literal and figurative guidance. Like them, he would spend his time in the woods, building both his body and his mind, through both sport and prayer. (Roosevelt became so close to these two men over the course of several trips to Maine that he would later enlist them to build and operate his Elkhorn Ranch in North Dakota.)

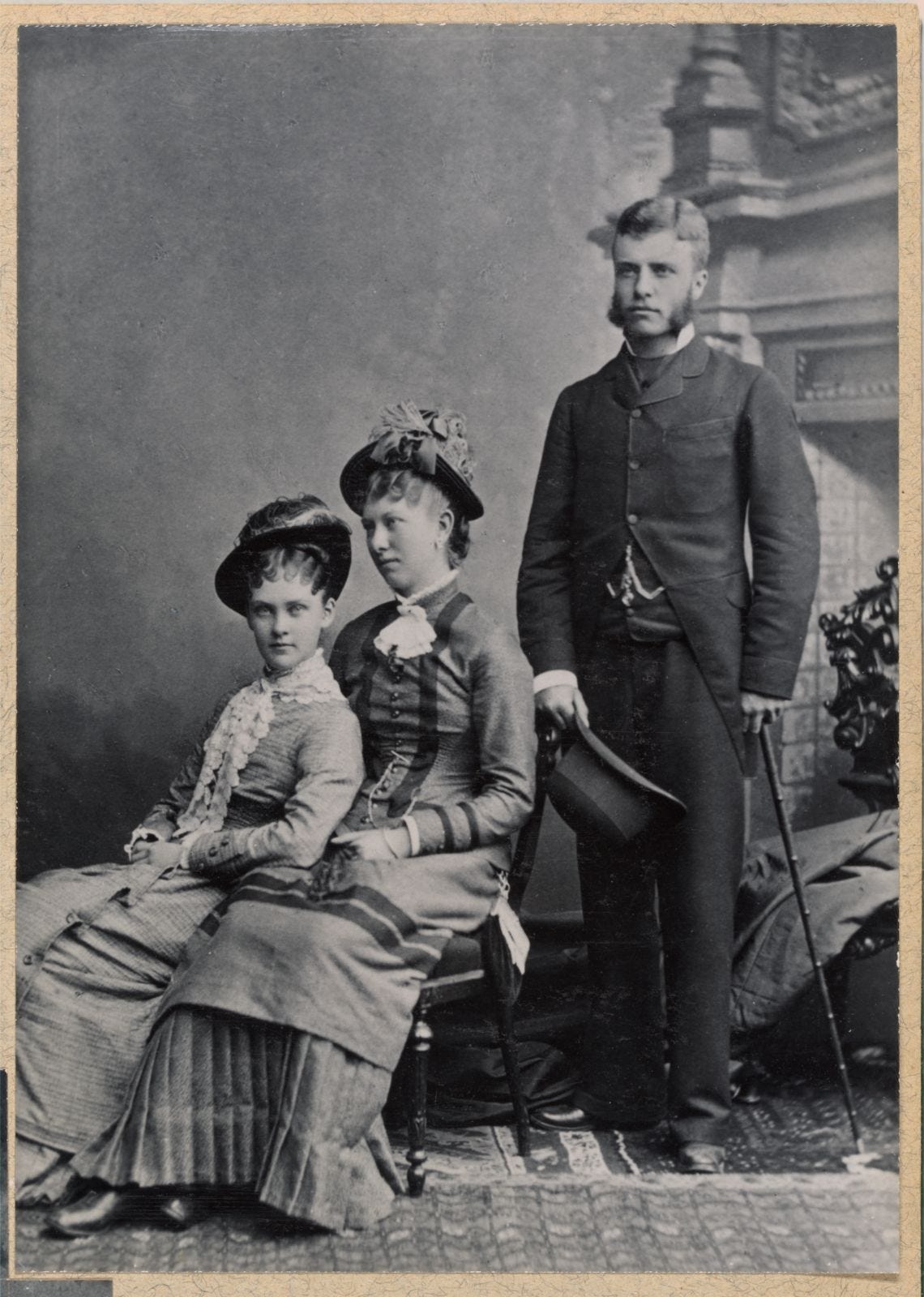

Reinvigorated, Roosevelt returned to Cambridge and delved back into his studies and social life. He joined the Porcellian Club (after a very public and painful fight between the A.D. and the Porc over who would get him) and spent twenty hours a week in the classroom. He attended social gatherings with his high-society friends, in particular the Saltonstalls and Lees. It was at one of these socials, in October 1878, that he was introduced to Alice Hathaway Lee, a remarkably beautiful girl both inside and out, with which Theodore was immediately and hopelessly smitten. He soon began what turned out to be a nearly two-year-long courtship, one marked by Roosevelt’s characteristic relentlessness in winning his prize.

Roosevelt was practically single-minded in his pursuit of Alice but did not neglect his Harvard career – in no small part because it would have dishonored his father’s memory. Over the course of his junior and senior years, Roosevelt continued to receive good marks (at least in the subjects he cared about) and became involved in several clubs, including the Natural History Society, the Finance Club, the Harvard Advocate, and the Harvard Athletic Association. All the while wooing Alice, who so enraptured him that he frequently described her as “bewitchingly pretty.”

Alice had resisted Theodore, perhaps even toyed with him, but by early 1880, he had finally won her and the approval of her parents. Their engagement was announced on Valentine’s Day. Following his graduation from Harvard, on October 27 – Theodore’s 22nd birthday – the two were wed at the First Parish Unitarian Church in Brookline, Massachusetts.

Although he’d spent much of his college career devoted to natural history and had become well-respected as a scientist, by the end of his time at Harvard, he would abandon his plan of becoming a naturalist. He had long found himself frustrated that natural history at Harvard focused more on laboratory work and theory than on the fieldwork that he found so invigorating. And Alice was not especially fond of the idea that he would be required to study abroad for three years to complete the program. (She was also among those who were sometimes disturbed by the creatures, both living and dead, that Roosevelt surrounded himself with.) And so, Roosevelt instead took up the law, which he saw as an entryway into politics. His rise like a rocket was soon to begin.

This was a great introduction! I loved the details about his education!

Roosevelt stuck to his own kind at Harvard, rather to be expected at that time; I was amused to see that his closest friend was a Minot.

My theory about Edith is that Roosevelt didn't like being told what to do, thought she was a bluestocking - and simply wasn't attracted to her. But after his beloved first wife died, he found familiarity comforting.

There's a splendid 17th century family portrait of the Saltonstall family in England.